We’ve seen the headlines and we’ve heard the talk of GCSE’s having ‘changed’ and become more ‘rigorous’. Let me attempt to demystify what exactly has changed and more importantly why.

Firstly, what has changed?

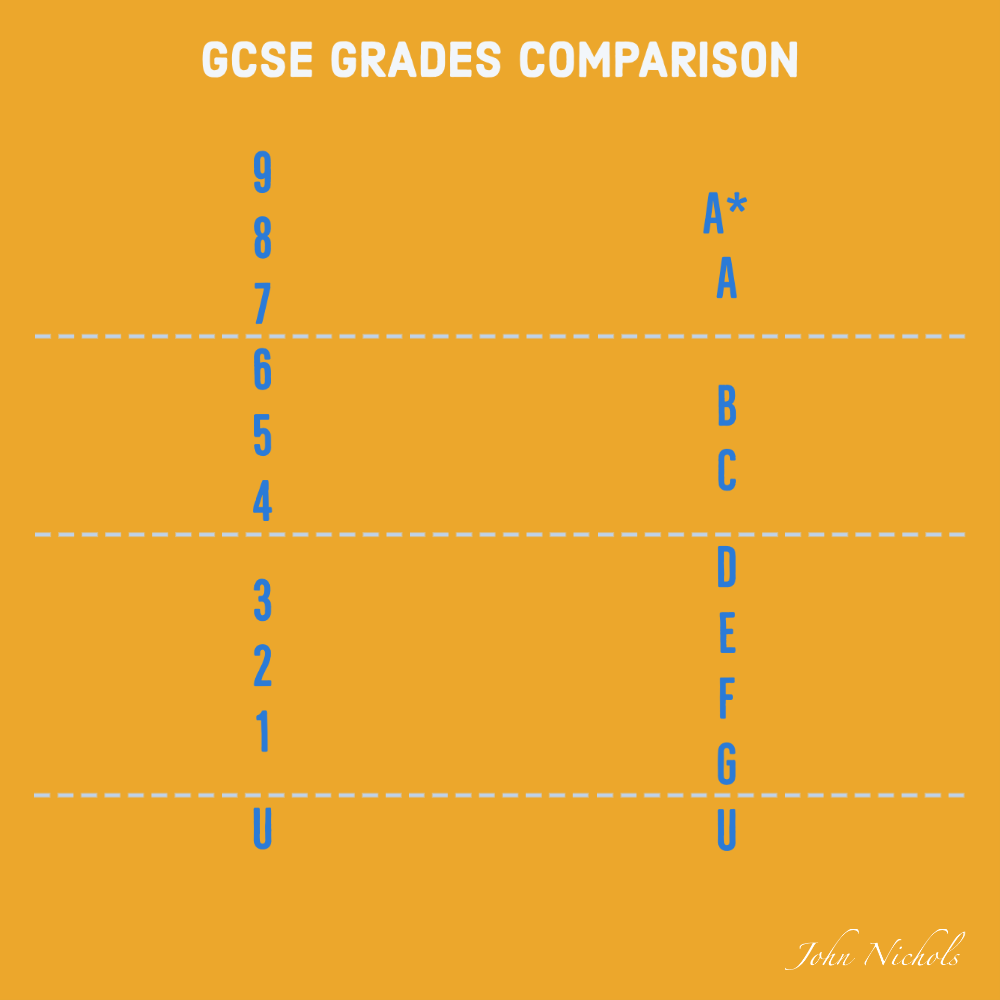

- No more A*-G grades, there is a new 9-1 grading system (4 is a standard pass, roughly equivalent to a low C and 9 is the top grade) By 2020, all GCSE exam certificates in England will contain only number grades from the 9-1 system.

- Most exams are now taken at the end of the two years.

- The content is more challenging and there is more of it.

- All students must do a minimum of two Science GCSEs.

- Coursework has been removed from most subjects.

Year 11 students who received their grades this summer were the first to take the new GCSEs in English Literature, English Language and Maths. The changes come as part of a government drive to improve confidence in the qualification. The Department for Education states “We have done this so pupils leave school better prepared for work or further study.” The government has also voiced their aim to match the standard of strong education systems globally such as Singapore and Finland, to name a few.

When did this happen?

The reform process began in 2011 with the national curriculum review in England. Wales and Northern Ireland are making changes to their GCSE system, but they are not adopting the 9-1 grading scale. One of the most important things to ensure is that everyone from students to parents to colleges to employers are clear on these reforms and what the new GCSE grades mean. As a result, a lot of money has been spent on explaining and publicising these reforms.

Why has it all been changed?

Associate Director of Standards and Comparability at Ofqual, Cath Jadhav, explains that usually about 60% of students achieve a B or C grade. By dividing grades up even more it will be easier for teachers, colleges and potential employers to differentiate between the good and the great.

The UK has been perceived to be falling behind other countries on international educational rankings. The Programme for International Student Assessment rankings (Pisa) are based on tests in Maths, Reading and Science taken by 15-year-olds in over 70 countries. The tests are taken every three years and the UK continues to fall short of the top performers. This has prompted the government to work on GCSE reforms that would enable us to catch up on a global scale.

Have vocational qualifications changed as well?

The ‘Wolf review of vocational education’ (March 2011) considered how the DfE could improve vocational education for 14 to 19 year olds. Of her 27 recommendations, there were four main principles for reform:

- The system must stop ‘tracking’ 14 to 16 year olds into ‘dead-end’ courses.

- The system must be made honest so young people are not pushed into damaging decisions.

- The system must be dramatically simplified to remove perverse incentives.

- We should learn best practice from countries doing things better than us, such as Denmark, France and Germany.

All these elements have played a part in where we are today with the changes. Despite the lack of clarity and uncertain future of the reforms, the main aim of them was to equip our young people more efficiently to compete in the global workforce.

What does this mean for students, parents and schools?

Students taking exams in the coming years will generally have to learn more content than they might have done if they had sat the old qualifications. At the same time, they would have gone through their first years of schooling when they were expected to take the old exams, so there will be a steeper learning curve for many students over the next few years. This means that it is even more important for educators to keep track of what each student understands and any areas they might be falling behind, in order to help them reach the standards required of the new exams.